(Transcript of my talk at ALTC24 on 3 September 2024)

Hello everyone.

Thank you all for coming. It’s a pleasure to be here.

I’d like to thank the ALTC24 organisers for this opportunity – thank you very much indeed.

My name is Matthew Moran, I am Head of Transformation at The Open University in the UK.

And this session is entitled ‘Reimagining learning-technology futures with speculative design: a hands-on workshop’.

To get us started, I will give a short introduction, and introduce you to speculative design in general, and some design techniques in particular.

But the best part of this session will be you getting hands on with the techniques, and working together to imagine and storyboard hopeful technology futures.

I’m going to equip you with a design canvas that you can take away and use collaboratively, in your institutions and communities, to imagine, and prototype, and start to build, positive technology futures.

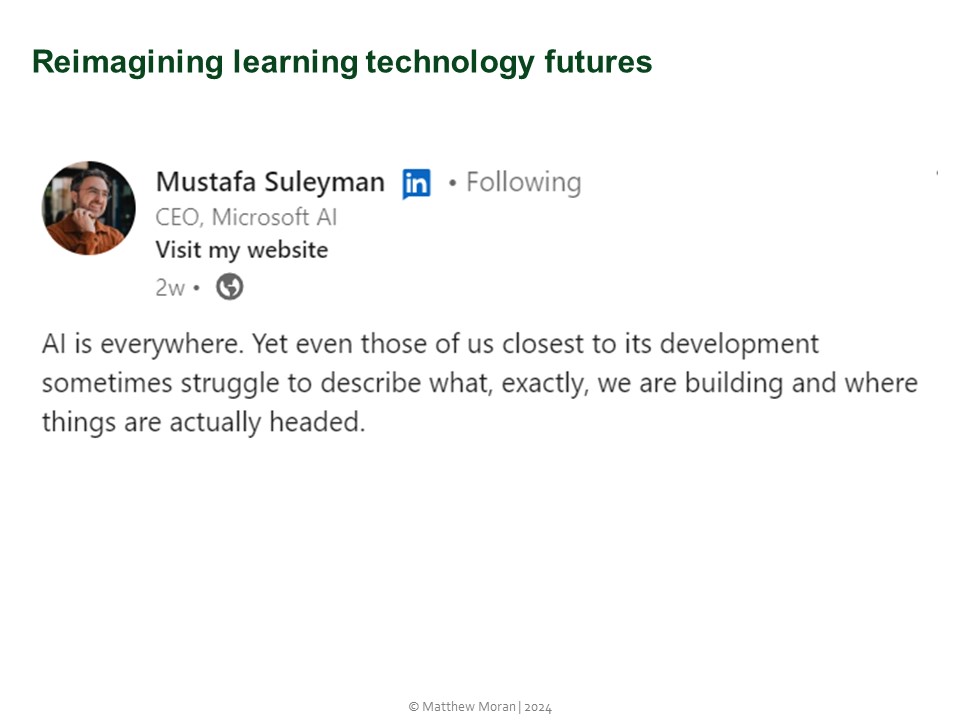

Of course, we hear a lot right now about ‘AI and the future of education’. But here is Mustafa Suleyman, the co-founder of DeepMind, now CEO of Microsoft AI. And here he is saying that, quote, even those closest to AI development sometimes struggle to describe what, exactly, we are building and where things are actually headed …

And what this tells us is that the future is not set.

The future is not predetermined.

The future is to play for.

Despite all the many proclamations and predictions about generative AI and its impact on the future of education in the last 24 months, the path forward is not clear or obvious.

The future, at least to some extent, is our choice. We can choose to accept whatever future comes along, whatever future is decided for us by tech companies and governments.

Or, we can choose to imagine and design together the better futures that we want.

And the speculative design techniques that I am going to introduce you to are a powerful means to do this.

These techniques are being used by artists, designers, responsible innovators and technologists, and by environmental and social activists, and now by educators, to reclaim how the future is shaped, and to imagine, prototype and build better, fairer, regenerative and hopeful futures.

We call these design approaches speculative.

And we call them speculative because they provoke us to imagine, and to visualize, and to describe, new realities and potential future worlds.

Speculative design enables us to imagine new possibilities – new possibilities that are, perhaps, more fair, more inclusive and more sustainable than what we have now.

Of all of the speculative futures design approaches, probably the easiest one to get started with is science fiction prototyping.

It’s quick to learn, easy, and fun to do.

So, what is it?

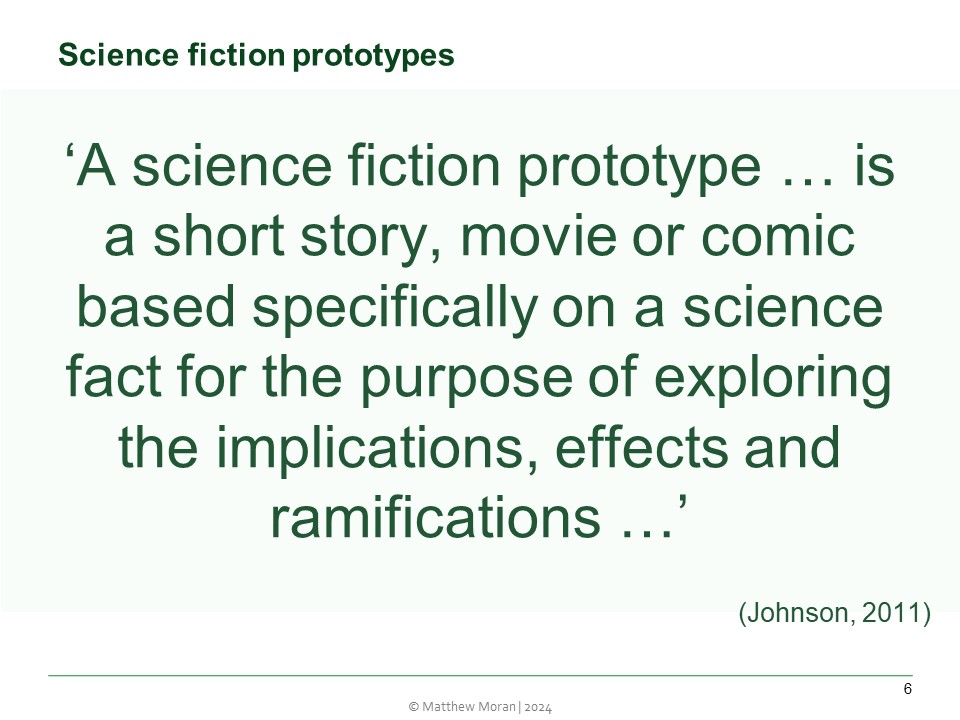

David Brian Johnson defines sci-fi prototyping as follows:

‘A science fiction prototype … is a short story, movie or comic based specifically on a science fact for the purpose of exploring the implications, effects and ramifications of that science or technology …’

In other words, sci-fi prototypes are stories, fictions, about a particular technology, a technology that already exists or may soon exist. And in making sci-fi prototypes, we are prototyping the implications and outcomes of this technology in society.

Typically, science fiction prototypes centre on a specific technology – an existing or near-future technology. And technology companies like Apple use sci-fi prototyping in the early stages of new product development.

But we can also create prototypes for other innovations, for change initiatives and change programmes, and new institutional strategies — any kind of change from the status quo.

We call them science fiction prototypes because they follow the classic formats of sci-fi – that is, your science fiction prototype should be in the form of a short story, or a comic, or a movie (or video).

Most people find that short stories are the easiest format to get started with, and they are fun to ideate, plot and write together collaboratively.

And we are going to have a go at collaboratively developing some sci-fi prototypes later in the workshop part of this session.

Another speculative design approach is design fiction.

Design fiction originated in industrial design at the end of the 20 century. The purpose of design fiction is to imagine, and to feel into, possible futures through material culture — with tangible artefacts that represent the symptoms and implications of change.

While science fiction prototyping uses stories, design fiction uses objects.

It is a physical way to tell stories about the future. The stories are told by and through objects, or devices, or products that might occur in a given future scenario. They give us a tangible experience of being in different worlds, experiences that we can see, feel, touch and taste — like this, one where flavoured snow falls from artificial clouds.

As Julian Bleecker, one of the leading exponents of design fiction, describes it, design fictions are ‘part story, part material, part idea-articulating prop, part functional software’.

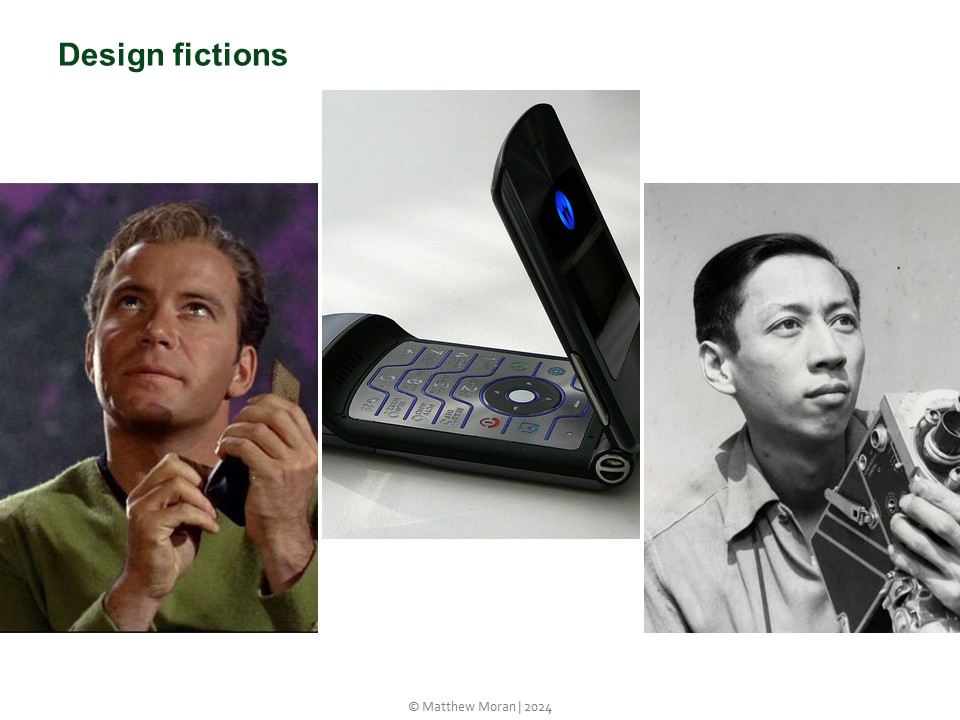

To give an example, in Star Trek, the classic sci-fi TV series, the characters use a ‘communicator’ device, a prop designed by Wah Chang (here on the right), which was space-age at the time of its creation, but which now looks remarkably familiar, as the flip-open folding design has been copied by designers of mobile phones for several decades.

But the aim with design fiction is not to produce functioning, marketable products.

Instead, the aim of design fiction is to propose provocative future scenarios where the implications of technology and design are deliberately exaggerated, and accentuated, in order to provoke – to provoke attention towards, and deliberation and discussion about, technological futures.

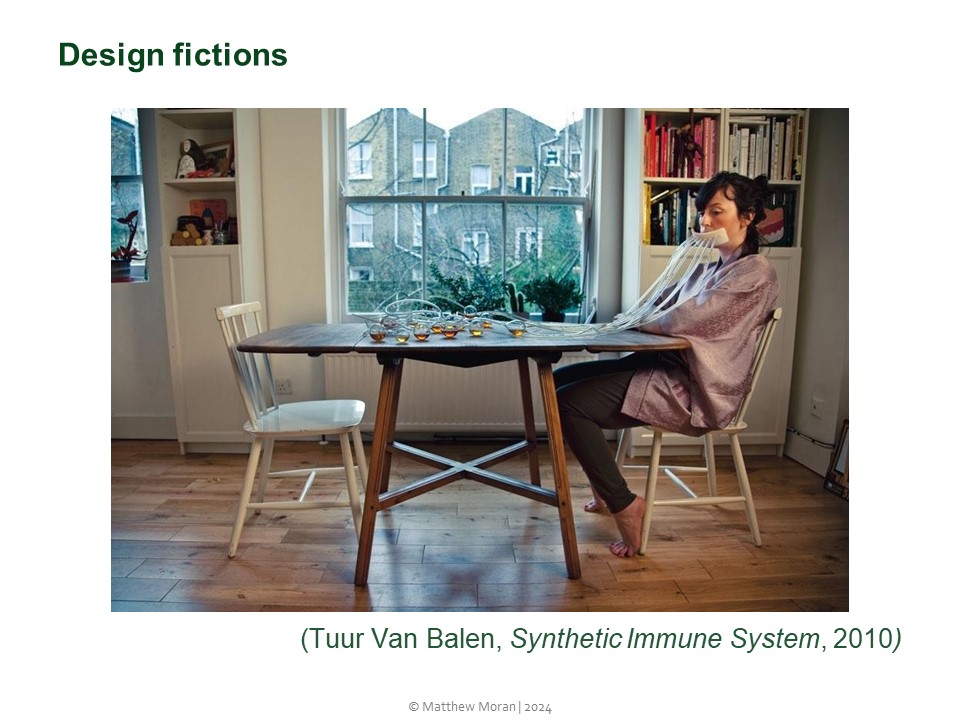

As in this image, which shows a synthetic immune system. This is a design fiction that accompanied a university research programme that investigated how certain metabolisation processes might be outsourced to micro-organisms outside the body.

Design fiction is design for debate, not design for production.

Consequently, design fiction has been taken up by responsible innovators as a means for inclusive public engagement and dialogue with emerging technology, particularly risky and controversial technologies.

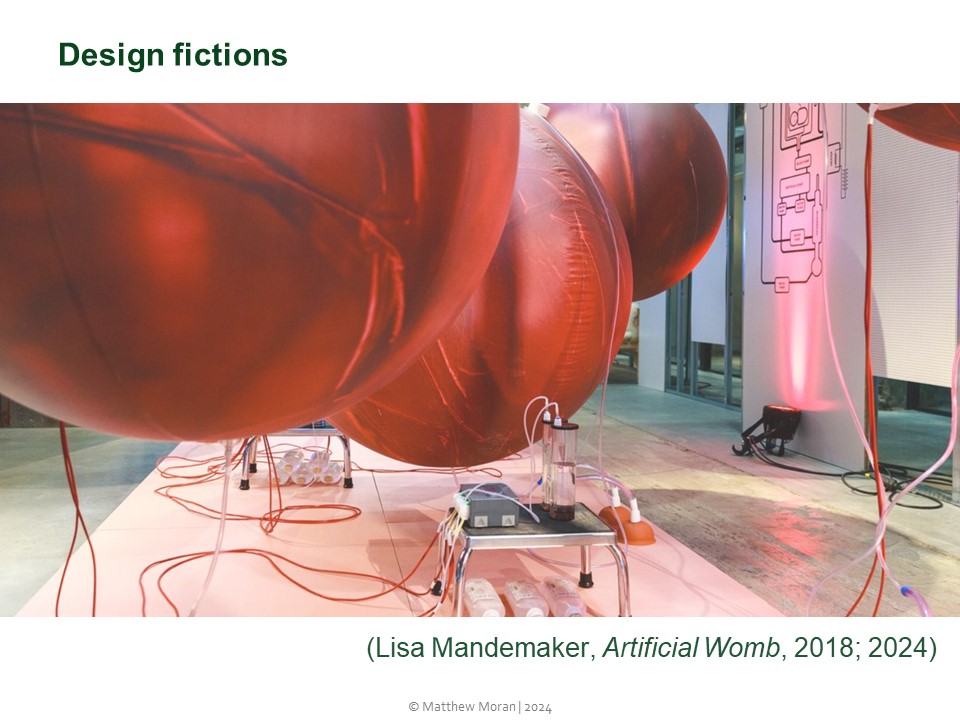

This is an installation at Dutch Design Week in 2018 showing how an artificial womb might be designed.

The installation was created by the artist Lisa Mandemaker as part of a research programme at Eindhoven University of Technology, to create an artificial womb for treatment of premature babies.

The installation provokes us to consider how these artificial wombs might be designed, and it creates a space for us to deliberate together on the consequences and implications of this technology.

Speculative design seeks to enable transparency, interaction and mutual responsiveness between innovators and societal actors, by anticipating the longer term social and cultural outcomes of technology innovation.

Contrast this approach to the irresponsible imposition of generative AI on global society without including people or considering the consequences and outcomes.

Speculative design is design for debate, not design for production. We do speculative design in order to generate ideas and deliberate on the challenges and implications together.

OK, let’s do one more quickly.

Our third speculative design approach is experiential futures.

Experiential futures takes design fiction further, by creating immersive scenarios which involve role-playing and simulation, to provide embodied, multisensory understandings of imagined futures.

The approach was pioneered in the late 2000s by the futurists Stuart Candy and Jake Dunagan. In Candy’s words:

‘An experiential scenario is a future brought to life.’

Experiential scenarios have been used particularly by architects, urban designers and city planners, and by artists and activists, over the last 20 years.

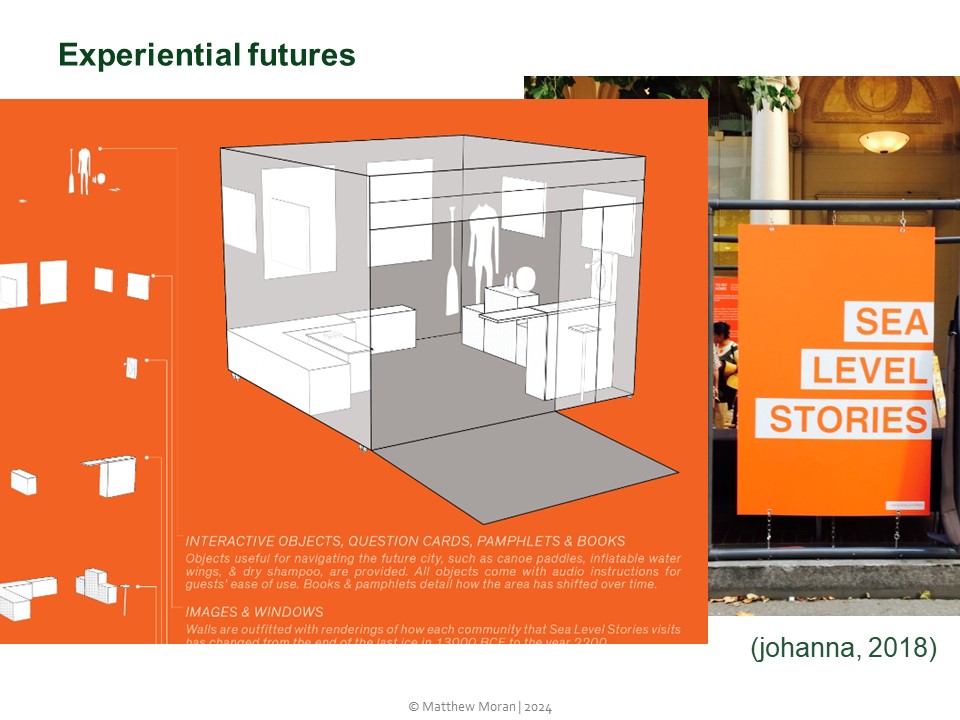

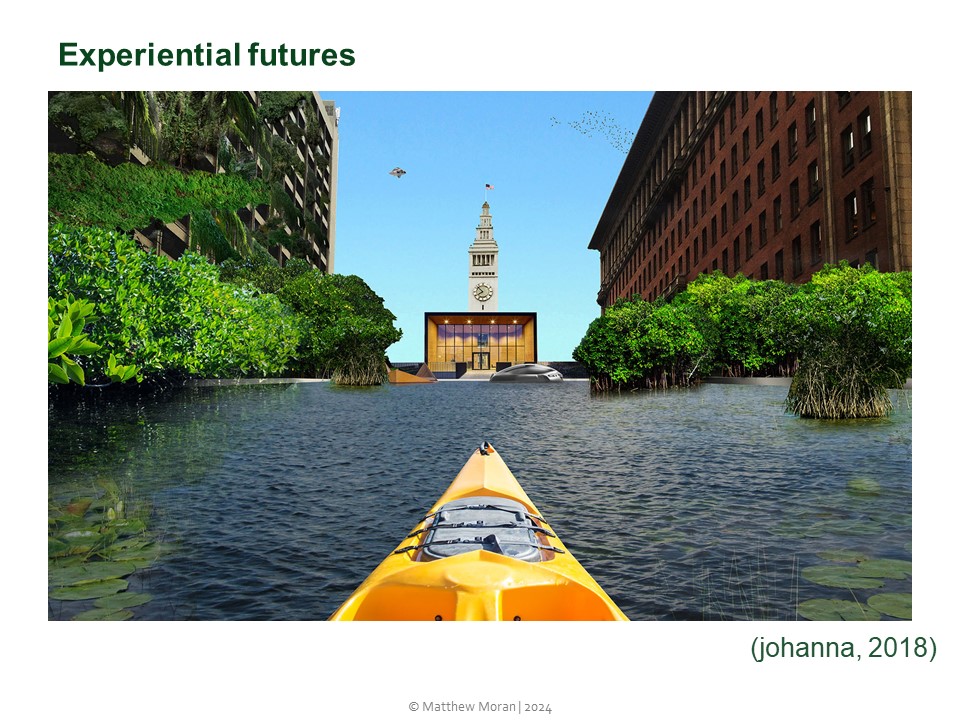

‘Sea Level Stories’ is an experiential scenario developed by the architect Johanna Hoffman in 2016. Sea Level Stories is a multimedia installation that simulates an AirBNB rental in San Francisco in the year 2200 (22 hundred).

We are renting an apartment for the weekend, and we are preparing to go outside to pick up some shopping. We put on our wetsuit and air-filtration mask, before picking up our canoe paddles to venture out into the searing heat.

And out the window there are views of how parts of the city have changed.

Hoffman’s purpose here is to create a space where we can vividly see, and feel, and act out the kinds of adaptations that humans are going to have to make as cities like San Francisco see rising sea water and extreme heat.

Like the other speculative techniques, experiential futures seek to collapse the distance between today and tomorrow, and create experiences that prompt us to reflect on the ramifications of possible change, and so consider our decisions and actions today.

The purpose of these approaches is not to predict a single future, but to imagine, experience and feel multiple possible futures, and to discuss and debate what we want our futures to be like, and what we don’t want them to be.

OK.

So that’s a very short introduction to some of the foremost speculative futures techniques.

But you have come for a hands-on workshop, and I am going to give you a hands-on workshop.

And for this we are going to use a technique I call reverse sci-fi prototyping.

Now, classic sci-fi prototyping, as introduced earlier, is a great technique to use if we are developing new technology, and new products and services, as it gives us a way to envisage and work through the possible near-term effects and longer-term consequences and outcomes of a new technology. And for this reason, sci-fi prototyping and other speculative techniques are now used by the likes of Apple, Amazon, Intel, IBM and others.

So if you are developing new technologies, and new systems and products, it’s a great tool to use.

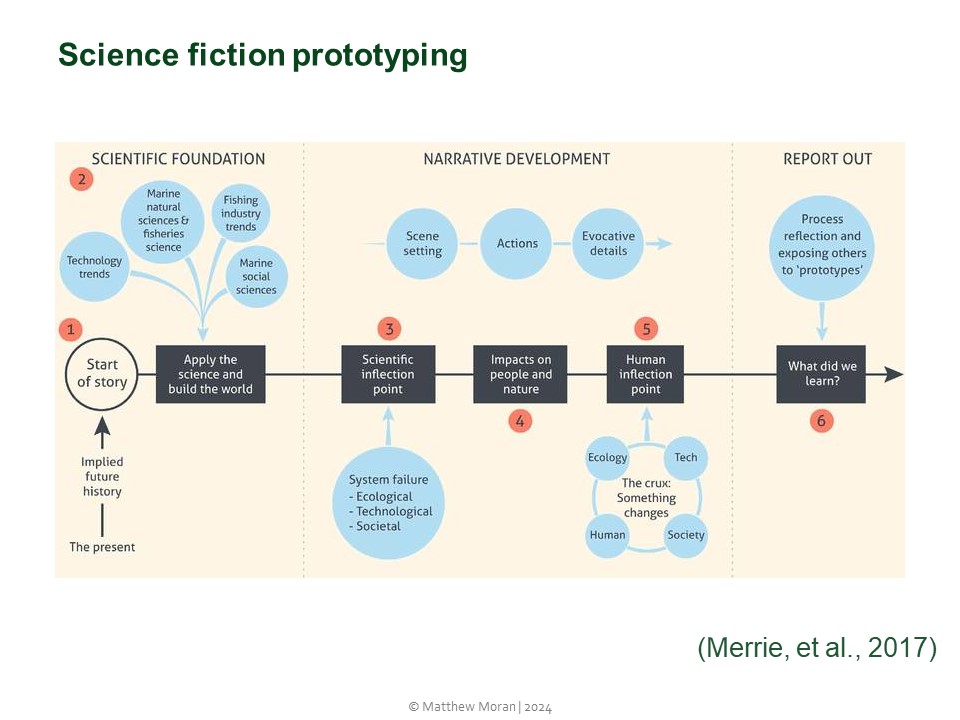

But sci-fi prototyping also tends to put technology first. The slide shows a diagram that illustrates the process of developing a science-fiction prototype in detail. As the diagram indicates, it’s a linear, left-to-right, process, which begins with the chosen science or technology, and works forward to effects and outcomes.

When we do sci-fi prototyping in this way, we start with technology, we prioritise the technology, and work towards the outcomes.

By contrast, reverse sci-fiction prototyping starts with the outcomes we want to see, and works back to the technology.

Used in this way, reverse sci-fi prototyping supports and enables the futures we choose, rather than driving potentially iniquitous, divisive, degenerative futures that we don’t want.

OK.

So what is sci-fi prototyping and how do we do it?

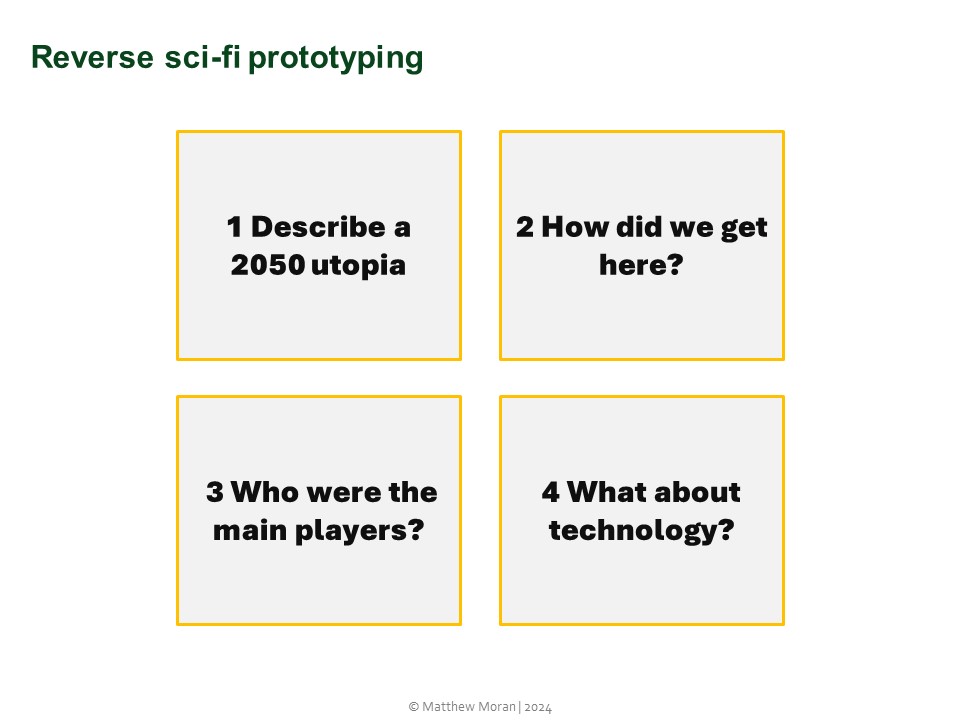

Here’s how it works briefly:

First, we are going to imagine a near-future world where education is thriving. The year is 2050 and education is in great health. We have overcome many of the problems and challenges that appeared to be so desperate in 2024. Access to education has become more free and fair, outcomes more equitable, the overbearing influence of ‘big tech’ has been controlled, and ethics, equity and responsibility are no longer afterthoughts chasing after out-of-control technology juggernauts, but are central to everything we do.

Whatever you want it to be: I am inviting you to imagine your own ridiculously optimistic near future vision of education, based on the challenges and issues you face right now. What does a really great set of outcomes look like for you in 2050?

Step 2. How do we get here? Next, we are going to think through what happens on the journey to 2050. What were the main steps we took to get here? What decisions were needed? Who made them and when? What decisions didn’t we make? What are the social, economic and cultural shifts that enable us? And what are the trends that run counter and that we have to resist and overcome?

Step 3: Who are the main players? Next, we are going to think about the protagonists. Who are they? And where is the main action located? Who does what and when? What tools do they use, and what other support do they draw on?

Step 4: Technologies. Finally, what role does technology play? What new technologies do we create that contribute to our 2050 utopia? What existing technology do we adapt and take with us, and what technologies do we leave behind?

Using the hard-copy canvases on the tables, what we are going to do is to develop some PLOTS for our reverse sci-fi prototypes. There isn’t time here to write it in full – you are going to speed plot it together in 20 minutes or so.

Usually, if I were doing this with teams or groups, you’d have at least a half day for this, so this is really intended to get you familiar with the tool, so you can take it away and do this work in your institution or community.

And I am deliberately asking you to be hopeful and positive in this activity.

I’m inviting you to imagine a near future of education where we win.

It’s very easy to do this work and get stuck feeling hopeless and negative, and often this results in pessimistic and dystopian futures which are not all that useful as guides to creating the better futures we want.

So for today, I am asking you to be ridiculously positive and optimistic.

And in half an hour’s time I want you to come back from the future saying, ‘We won’.

…

There are two additional steps in the reverse sci-fi prototyping process.

Step 5 asks what have we learned?

What useful learning can we take from our prototypes to achieve the positive futures we choose.

Here we are asking particularly about the aspects of our future vision that are particularly strong and viable, and those aspects that are more weak and vulnerable.

And step 6 is asking what do we do next?

What do we have to do now to start working towards our chosen future? What is happening already that we can take advantage of, and what might work against us? What competing visions are there? And what do we have to do now, and next, to make sure that we win!

If you are interested in getting your hands on the full canvas I will be making this available exclusively to delegates of ALTC24 after the conference, initially as a PDF, and coming soon as a Miro.

To finish.

We’ve looked at a couple of speculative design approaches.

The purpose of these approaches is not to predict a single future, but to imagine, experience and feel into multiple possible futures, and to discuss and debate what we want our futures to be like, and what we don’t want them to be.

The process of designing these speculations is way more important than the product. Our goal in doing this work is to bring people together, to imagine together.

Speculative approaches enable us to collaboratively prototype, and test, and evaluate, and discuss, and shape the futures that we want to build.

So do it together. Doing this work together cultivates critical thinking about the present, and ignites our imaginations about what lies ahead.

It builds trust and cultivates connection.

Finally, don’t be surprised if using speculative design approaches makes you uncomfortable. It should. But it should also give you back your agency to design better futures together.

If you would like access to the reverse sci-fi prototyping canvas to use in your institutions or communities, I am making this available to ALTC24 delegates.

If you are interested, please email me at matthew dot moran at open dot ac dot uk

I hope you will want to try out speculative futures design with your colleagues and students, and I hope you have a lot of fun with it when you do.

I’d love to hear how you get on.

And if I can help you with your futures designs, I’d be delighted, so please feel free to contact me.

Leave a comment